Physically Based Rendering, online

Today, Wenzel, Greg, and I posted the complete contents of the third edition of Physically Based Rendering online, free for everyone. We’re thrilled to be able to make the content of the book freely available and plan to publish updated versions of the book roughly once a year as we do our best to keep up with advances in rendering.

Reaction to the news was quick and mostly along similar lines:

An /r/programming reader on the release.

Just kidding; people seemed really happy about it.

Motivations

The idea of democratizing access to information has always been dear to me; that idea always motivated my own work on the printed book—do my part to make this fascinating area accessible to as many people as possible. With the previous instantiation of the book, though, there was still some barrier from the book’s cost—no big deal for professionals in developed countries, but a real hurdle for many students and for people in developing countries.

Once a month or so an email comes in to the [email protected] alias from someone who can’t afford the book and is thoughtful enough to ask if it’d be ok with us if they looked for an illicit copy online; those were always tough emails in that “sure, go ahead see what the warez sites have” was an unsatisfying answer to consider typing up and sending. Most were left unresponded to.

Beyond making it easy for those people to have access to the book, I also really like the idea of adding high-quality free content to the Web. It’s saddened me how the Internet has turned into a cesspool of ads, ad trackers and click-bait, a gurgling pool of stink that offers a website that can offer validation to any point of view, no matter how ridiculous or reprehensible. Part of me thinks the Web is a lost cause at this point, and quite possibly a danger to the survival of humanity, but as long as we’re all still here, I like the idea of a small strike against what it has become.

On a more optimistic note, the Web browser, especially in today’s era of WebAssembly, offers impressive possibilities for adding interaction to how the ideas in the book are conveyed. We’ve just scratched the surface of that, using jeri to make it possible to interactively examine and compare the rendered images we use to make various points along the way. I expect we’ll do much more with interaction in the future.

My one worry about this step is the belief that computers aren’t a very good medium for long-form reading. Getting through Physically Based Rendering in a way that one gets the most from the experience requires time, patience, and attention. It’s hard to hold onto the focus required when facebook beckons from the next tab over, but I still think the positives will more than outweigh the negatives.

With the contents book now online, I thought it’d be fun to write a short history of how we got here.

Beginnings

Twenty years ago, Pat Hanrahan wasn’t happy with the content of the available rendering textbooks. Ever since the 1990s, he’d been teaching a course on rendering that had a strong physical foundation; nothing on the market fit that mark.

He knew that Greg Humphreys and I, students of his at the time, were interested in both rendering and literate programming. Around 1998, he made us the offer that if we wrote a ray tracer as a literate program, he’d use it in his course and that’d help hone the book. Greg and I had no idea what we were getting into. We were grad students so time was infinite and so we said yes. (As a measure of our delusions about what we were getting into, we had the idea that after this one, we’d write a second book—a literate program about how to implement a rasterization pipeline like OpenGL.)

Pat’s support was critical—his feedback about the drafts and the ideas he encouraged us to incorporate were integral to the book’s success. At the start of the project, Pat was listed as the third author on the manuscript; he eventually dropped off, insisting that his contributions weren’t enough to warrant being listed as author. At the time, I worried a little bit that it was a sign that he wasn’t happy with how the book was turning out. I’ve pretty much gotten over that by now.

I’ve dug up two early PDFs of drafts of the book. The first is from 2001; looking at it now, a few things about it are remarkable to me. One is how there are paragraphs and code here and there that have remained in the book to this day. Another is how little “physically based” there is in it compared to the final first edition. The draft ends with a simple little path tracer, but that’s about the extent of it.

Not a professional illustration, from the 2003 draft.

A draft from 2003 is much closer in form to the first edition. There are still plenty of “XXX TODO”s and terrible hand-drawn figures, but you can certainly see the bones of the book there (as well as things like the start of a bidirectional path tracer that didn’t make it in the end).

Morgan Kaufmann: the first edition

As the book started to feel well-baked, we started reaching out to publishers. Our first choice was clear: Morgan Kaufmann. Not only had they published a slew of classic books in computer science—from Hennessy and Patterson’s Computer Architecture to Glassner’s Principles of Digital Image Synthesis—but from my perspective as a reader, they’d always been with the highest production standards. We hoped to be a part of that lineage.

I was thrilled when Tim Cox, an editor at Morgan Kaufmann, immediately latched on to our proposal—I was worried that “literate program” would be a step too exotic for a publisher, especially since there wasn’t a history of very many published literate programs. I remember the process being remarkably straightforward—going from “Hey, we’ve got this book draft, what do you think?” to “Let’s make this real,” remarkably smoothly.

And then as we got into it, it was delight after delight to understand what it meant to do a book well, with professionals who lived and breathed this stuff. A range of experts joined in—copyeditors and proofreaders and indexers and illustrators. Elisabeth Beller, the project manager, was particularly integral to making the process work so well.

Paul Anagnostopoulos played a critical role as the compositor. The compositor owns the book text during production: it’s out of the authors’ hands as once editing and proofreading starts, and the compositor takes care of pulling together the text and the corrections and applies the art of laying it out well on the page.

The compositor’s role is usually outsourced these days, but Greg and I insisted that that we have someone excellent and nearby doing it. Our concern was specifically the dense link structure of the book: the printed book has mini-indices on each page that show where each source code identifier is defined in the book. Further, code fragments include page numbers indicating where they’re defined and used—it’s a ton of indexing that has to be automated and gotten right; if it’s wrong, most of the value of the book is lost. This was no regular compositing job. Paul took care of all of that perfectly, with impressive attention to detail. That work was critical to the book turning out as well as it did.

Working with a professional copyeditor (Ken DellaPenta) and proofreader (Jennifer McClain) was a delight: a “thence” where we should have used “whence” and a multitude of further corrections, big and small, that also taught me many new things to pay attention to in my own writing.

Another example from the editing phase: in the introduction, we’d written that in equations, we’d use italics for variables and Roman text for abbreviations in formulas. 800 pages later, the proofreader remembered that and saw that our regular use of an italicized “a” for σa as the volume absorption coefficient was a mistake, since the “a” didn’t represent a variable but was short for “absorption”. Absolutely correct, and never noticed by the rest of us. It may seem a small thing, but I believe that getting those details right adds up to make a real difference.

There was but one misstep in our interactions with Morgan Kaufmann. The book was to be part of Morgan Kaufmann’s “Series in Interactive Technology”, which at the time seemed an off fit, though now can be seen to be remarkably prescient. To us, it didn’t seem to matter much which collection of books we were a part of, so we didn’t worry about it.

Then the proposed cover arrived, styled to match all of the other books in that series. I saved it, a treasure in my files:

Yes, that is a tiny joystick in the middle of the cover.

After receiving the cover design and then after a few deep breaths, we explained that it wouldn’t do—that as a book on rendering, really, it had to have a nice rendered image dominating the cover. That point was quickly understood, and happily, an exception was made.

The second and third editions

The second and third editions, which came out in 2010 and 2016, respectively, were done with Elsevier as the publisher, which had purchased Morgan Kaufmann along the way. From the start, the tone was a little different: a little more “let’s get this done”, and a little less “let’s get this right”. The people involved were all perfectly nice and well-meaning; I suspect that the shift was due to factors that were beyond their control.

During the book production process, we became accustomed to getting an email from one of the folks involved every few months: “I’m moving on to a new role; I’ve CC’d the person taking my place, who’s very excited working on the project. And don’t worry, nothing will change.” (And then we’d receive the same again a while later as the replacement was replaced). We worried a bit about what this churn might mean for the quality of the printed book, but it all turned out fine in the end.

Two things happened with the third edition that have brought us here. First, the index. With the first edition, we discovered how excellent an index could be when done a professional indexer. (How marvelous that there is such a thing.) Though our indexer, Steve Rath, wasn’t a domain expert in computer graphics (something that worried me at first, because I had no idea), from him we learned how having the right systemic approach to categorizing the ideas in a book was an art of its own and far more important than expertise in the subject area.

For the third edition, the indexing was apparently sent offshore, and calling it “slapdash” would be too generous. Nearly a quarter of the entries in the provided index were blatantly wrong—wrong like “we actually removed that topic in the third edition”, or “that page number doesn’t exist.” Just as disappointing as the quality of it was the fact that no one on the Elsevier side noticed: here you go, we’ve got an index, let’s start printing. Wenzel and I hit the big red button, extracted two weeks delay in the schedule, and did our own index.

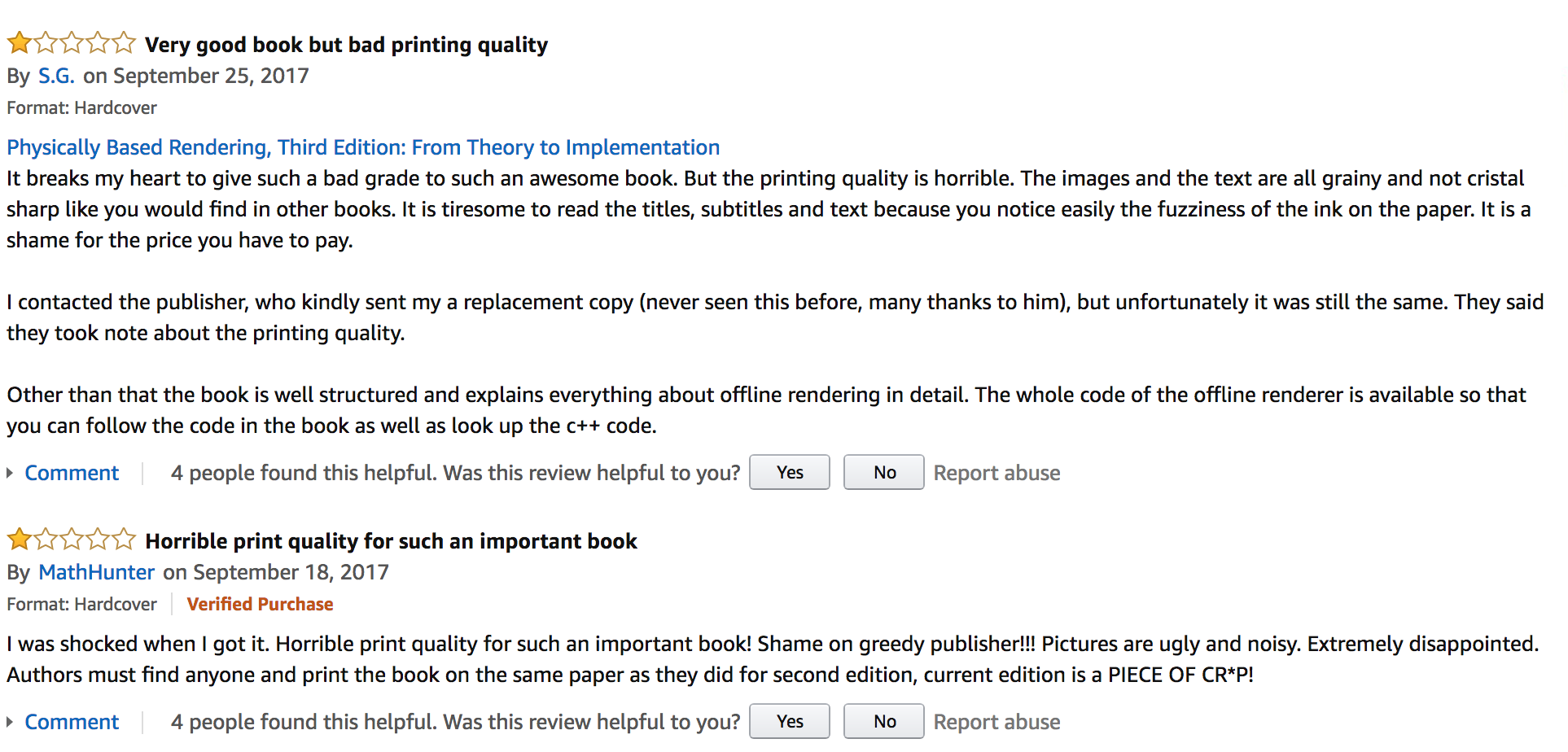

And then there was the second printing. The first printing of the third edition sold out quickly, and so another print run was done, books were shipped out to the world, and then this:

It was a terrible feeling, having put endless hours into the book, putting in all of our own best efforts to make the very best thing we could, and then having something awful being put in readers’ hands. We had no control of all sorts of details beyond the text itself, which would have been fine, if we were confident that the publisher was on top of them.

I mean, apparently no one even looked at the books that came back from the printer before it was put on the shelves.

Getting the rights and going online

After the printing debacle, we asked for a “reversion of rights”, as it’s called in the biz—the transfer of the copyright of the book text back to the authors. Happily, the publisher agreed. Papers were signed and the text is now ours. They’ll continue to sell the copies they have as well as the PDF and Kindle editions, but we now can do what we like with the text.

While we may end up working with a publisher in the future (or, perhaps publishing ourselves—I always loved how Edward Tufte did that with his own books to ensure the quality he wanted), we took this turn of events as an opportunity to see what an online version of the book would look like.

Starting from a very rough proof of concept from an exploration of the idea

of an HTML edition a few years ago, we started hacking and polishing: it

was hundreds of small tasks along the lines of making the URLs include the

chapter names and section names and not just be “ch04s05.html”, figuring

out the right place to put equation numbers (the right column margin in the

end), wiring up all of the ids and hrefs so that following links took

you the right place, figuring out how to use Bootstrap so we could have a

navigation bar at the top of the screen, and so forth. Something was

learned about the DOM and about CSS along the way, and in the end we had

something we were happy with.

We all hope that readers will be happy with it as well. We’re happy to hear feedback and suggestions about the book’s presentation in this format (that’s “[email protected]”.)