The story of ispc: retrospective (part 11)

With the open-source release, I hoped that ispc would sow the seeds of its own oblivion. I hoped that some day it would be upstaged by a better SPMD on SIMD compiler, ideally one that was part of widely-used compilers like clang, gcc or MSVC. I like ispc a lot and enjoy writing code in it to this day—I still think it’s a nifty tool. True success would have been if someone had taken the idea and did it better, making the approach available ubiquitously.

At least ispc survives and seems to have happy users; I’m thrilled about that. And I’m glad that Intel has a few people working on keeping ispc going. The Intel folks have been great about getting AVX-512 working well and fixing bugs that users have found.

Today ispc generates beautiful-looking AVX-512 code; here’s a bit of aobench, featuring those sweet zmm registers and some AVX-512 mask management:

vsubps %zmm6, %zmm16, %zmm0

vsqrtps %zmm7, %zmm6

vsubps %zmm6, %zmm0, %zmm0

vmovaps 2368(%rsp), %zmm6

vcmpnleps %zmm0, %zmm6, %k1

vcmpnleps %zmm16, %zmm7, %k1 { %k1 }

vcmpnleps %zmm16, %zmm0, %k0 { %k1 }

kmovw %k0, %ecx

testw %cx, %cx

je LBB1_32

I should probably find some time to go have fun writing and running some ispc programs on an AVX-512 CPU.

Usage

At least a few large-ish systems have been written with ispc; it seems to have held up well.

I wrote a Reyes renderer in ispc that unfortunately never made it to the examples in the ispc distribution—I never finished it. It was nearly 10k lines of ispc code. I felt that ispc proved itself well: I was able to generate good SIMD code for just about everything the renderer had to do: evaluating Beziers when dicing, shading, texture filtering, rasterization, occlusion culling, and so forth. There’s no way someone could have written all that in intrinsics.

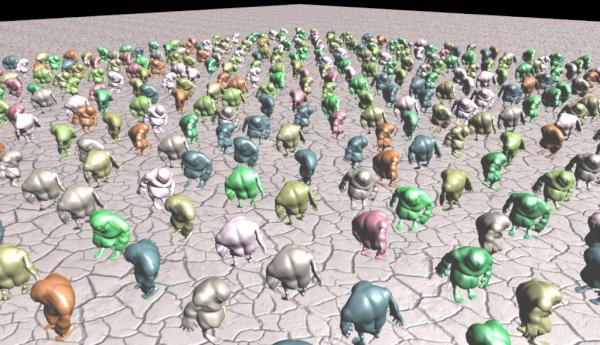

Digging through old tweets from when I was at Intel, I found this image it generated:

The scene had 1.4M bicubic patches; the ground plane was textured and displacement mapped. Rendering the scene at 720p with 16 samples per pixel took 634ms on a 4 core AVX1.1 system. That seems pretty fast to me.

Embree, Intel’s high performance ray tracing library, made extensive use of ispc. I was thrilled that they used it—some of the people in that group are ridiculously good intrinsics programmers; they have high standards.

DreamWorks went and wrote their new production renderer, MoonRay, using ispc. They wrote a paper about it that includes extensive measurements about the impact of vectorization. It was great to see that vectorization worked out well in a system of that complexity; it turns out—go figure—that this SIMD stuff is useful for more than just localized kernels.

Critique

Overall, I’m pretty happy with how the language turned out. It helped that there were specific programs that I wanted to write with volta; that gave a solid touch-point for making design decisions along the way. A small example: naturally I wanted to write a ray tracer in it, but maybe at first I’d just want to do ray traversal in volta. Therefore, making it easy to call volta from C/C++ and to share pointer-based data structures between the languages was a core part of the design.

Designing something to solve your own problems can be dangerous: worst case, it’s not useful for anyone else. But that’s better than designing something that’s of no use to you but that you imagine other people will want. I was pretty sure that the sorts of use cases I was considering would both fit things other people wanted to do in graphics, but perhaps also be applicable in other domains as well.

Built that way, I think that volta got a fair number of things right, though with more experience and perspective, it’s become clear there are a number of rough edges and areas for improvement, both in the design and implementation.

32-bit datatype focus: most of the computation I’m personally interested in doing turns out to be largely based on 32-bit floats. Those got the most attention when I was writing optimization passes and looking at compiler assembly output, somewhat to the detriment of 64-bit floats and definitely to the detriment of 8-bit and 16-bit integer datatypes in terms of code quality.

One SIMD vector width per source file: In ispc, the SIMD vector width is fixed on a per-source-file basis at compile time. However, it’s often useful to use a different SIMD width in different parts of the computation, for example when operating on differently-sized data types. It’d be nice to be able to vary that on a more fine-grained basis.

The unmasked keyword: ispc provides an unmasked keyword that can be

used when defining a function or before a statement; it lets the programmer

indicate that an “all on” mask should be assumed by the compiler at that

point. It’s a useful tool for programmers who want to shave every

unnecessary instruction when it’s safe to do some computation without

masking, but it’s dangerous and doesn’t really fit with the SPMD

programming model; it’s more or less a workaround for a hardware limitation

that leaked into the language.

Addendum: upon reviewing the

documentation,

I’m reminded that unmasked makes it possible to express nested

parallelism in ispc, which I guess ain’t such a bad thing after all, but

there’s probably a better way to do that.

Explicit vectors and SPMD: It would be nice to be have support for explicit vectors that are mapped to SIMD lanes and to split the SIMD lanes between SPMD and those. Not only would this make explicit vector computation available through the language, but it’d be possible to express computations that have a mixture of vector- and data-parallelism.

Embedding in C++: As discussed earlier, it’d be nice to have the SPMD functionality available in C++; that’d enable even easier interop with application code, and having the full power of templates, lambdas, and, perhaps, virtual functions would be nice to have available.

The unwanted pull request

As we approach the end here, I should apologize to a few folks at Intel for a pickle I put them in.

After leaving Intel, I came to Google and ended up working on things that ran on ARM CPUs. I thought it’d be fun to write a backend for NEON, ARM’s vector ISA. I did that during downtime in my hotel room at SIGGRAPH in 2013. It was just a few days work, following the same path described earlier.

I found and filed a few bugs in the LLVM NEON backend. After they were fixed, ispc for NEON worked, but the speedups were pretty unimpressive. Whereas ispc would reliably give 3-4x speedups for SPMD programs on 4-wide Intel vector units, 2x was more common on the ARM CPU I was using. It was something, but not surprisingly good in the same way it was on Intel CPUs. I thought it was still useful to make it available to other people, though; a number of developers had requested the functionality.

Although I still had commit rights to the github repository, I packaged up those changes into a pull request. I figured that ispc was Intel’s to maintain at that point, and they should decide whether the changes went in.

I couldn’t help myself, and at 1502 GMT on July 20, 2013, I posted two tweets:

Finished ispc NEON backend: github.com/mmp/ispc/tree/… Tests passing, examples work, etc. (aobench on a15 attached.)

Now waiting to see what the current maintainers do with the pull request. :-)

I definitely underestimated how sensitive the situation would be. I was later told that there was a flurry of discussion internally around it. I don’t think anyone wanted to be the one who accepted the pull request; there was zero upside and potentially a whole lot of downside to being the Intel employee who allowed ARM support to be added an Intel-distributed and branded compiler.

I particularly regret that the people who I put in that sticky situation were were folks who had been supportive of ispc and who had been keeping the project going. One of them sent me an email saying they wouldn’t accept the pull request.

At 2215 GMT, 7 hours after my first tweets, I tweeted:

Impressively quick pull request rejection.

I decided to just fork the repo; it seemed like a reasonable option.

Pushed ispc with NEON branches specialized for int8 and int16 computation: github.com/mmp/ispc/tree/…. Assume this branch will be long-lasting.

However, Jean-Luc Duprat, who had previously worked on adding support for Knight’s Ferry to ispc, felt that having it in there was the right thing—for users, and even for Intel. He was no longer at Intel but still had privileges to commit to the the github repository and so he went ahead and accepted the pull request. There it was: the NEON target landed in the official repo. To revert it probably would have been even more awkward, so there it has stayed. Jean-Luc lost his commit privileges shortly thereafter. I’m pretty sure he felt it was worth it.

The ARM support is still there, but it isn’t enabled in the official binaries from Intel. That seems like a fine way to slice it.

We’re not quite at the end. One short post tomorrow, where things get philosophical.