The story of ispc: volta is born (part 2)

As before, this is all from memory, but I’ve done my best to get it all right. If you were around then and see something I got wrong, please send me an email.

I’ve always really liked You and Your Research, a talk that Richard Hamming gave at Bell Labs. I try to re-read the transcription once a year or so; it’s full of great advice. One part that always stuck with me was a section about the curse of winning the Nobel Prize—that many Nobel Prize winners end up not doing any interesting work after receiving it.

Hamming’s diagnosis:

When you are famous it is hard to work on small problems. This is what did Shannon in. After information theory, what do you do for an encore? The great scientists often make this error. They fail to continue to plant the little acorns from which the mighty oak trees grow. They try to get the big thing right off. And that isn’t the way things go.

While I’m neither weighed down by a Nobel Prize nor a great scientist, I really like that insight. Better to fool around and explore things and not start out with a grand plan, but be ready to focus when that exploration gives you an interesting direction to take.1

programmering i sverige

I spent the summer of 2010 in Sweden, working with Tomas Akenine-Möller and the amazing brain trust he had assembled. That group of five collectively knew more about rasterization and real-time rendering than just about anyone in the world; at the time, they had all sorts of interesting work afoot on efficient high-dimensional rasterization for motion blur and defocus blur.

They welcomed me with a small present, pictured below. (Also: potatoes and fresh dill.) At the end of the summer, I confessed that I hadn’t eaten the pickled herring, though had happily made my way through the aquavit. My recollection is that most of them agreed that pickled herring wasn’t all that tasty and that they hadn’t expected me to actually eat it.2

While I was in Sweden, I started to fool around with LLVM, thinking it would just be a little acorn sort of thing, quite likely something that would go nowhere. Digging into LLVM was another thing that happened thanks to T. Foley, who was quite enthusiastic about its design and capabilities.

If nothing else, learning how to use LLVM also felt like something that would give me a useful new thing to have on my programmer’s tool belt. Steve Parker et al.’s paper on Optix came out that summer; they were JITing specialized high-performance ray tracers—a really interesting way of thinking about that problem, made possible by clever use of compiler technology. That was the sort of thing that could get me excited about code generation.

LLVM takes a mid-level program IR as input and takes it from there, optimizing and generating native instructions. It was appealing to think that if I wrote the high-level compiler stuff and the early compilation passes, then I could let LLVM take it the rest of the way to optimized assembly. That possibility made all this compiler stuff much more interesting to me, though I didn’t have a clear plan for where it would go.

Unfortunately, I didn’t end up doing as much deep technical work with Tomas and the others that summer as I’d hoped—still a small regret to this day. Part of it was the overhead of Intel meetings; each afternoon I’d head home early and get on the phone for a few hours to call into meetings that were starting in the morning back in the U.S., and part of it was my being off spending time hacking on the compiler instead.

I didn’t say a lot about my compiler hacking to them at the time; I still had no idea what it would turn into, and what I had at first didn’t seem all that interesting. To be honest, I was a little embarrassed by how uninnovative it was for the first few months, especially in contrast to all the really smart rasterization stuff that was happening around me.

The brief life of psl

As I started fooling around with LLVM, I needed a name for my compiler-to-be and some initial use-case. My first stab was “psl”, which stood for “portable shading language”. Portability per se wasn’t ever my biggest goal in the effort; in retrospect I’m not sure why I chose that name.

I started with a parser that Geoff Berry and T. Foley had written for a C-based language; in turn, I think (but am not positive) that was based on Jeff Lee’s lex file and yacc grammar for ANSI C. With that, I started writing a basic compiler that handled a subset of C, building up an AST, doing passes over it for typechecking, all that compilers 101 stuff. I wrote the code to turn my AST into LLVM IR (no additional intermediate representations for me!) and then whee, started seeing nice looking (scalar) x86 code.

I’d never written a compiler before, so all this was loads of fun; I was a lot more motivated to learn about all that compiler stuff than I had been previously, when it was less obviously useful for the programs I wanted to write myself.

My thinking was that the shading language might go somewhere interesting; I might morph from C to a neat little domain-specific language for shading that did interesting things. Maybe a future version of Physically Based Rendering would have chapter about this stuff—who knew? I tried not to worry too much about where it would go; it helped I was having loads of fun enjoying the nicely optimized instructions that LLVM spit out in the end even if my compiler was nothing special in its capabilities.

At some point I was curious to see whether LLVM would generate good SIMD code. I wish I remember why exactly I tried the experiment; it may have been a thought that it would be interesting to shade multiple points at once using SIMD with the shading language, but honestly I don’t remember.

In any case, I modified psl to treat scalar variables as 4-wide vectors, and compiled a little program to LLVM’s SSE4 target. I’m pretty sure the program was:

float foo(float a, float b) { return a + b; }

And bam, I got:

addps %xmm1, %xmm0

retq

It was incredibly thrilling—I couldn’t have asked for anything better.

From there it was easy to add support for a few more arithmetic operations—multiply, divide, etc., and as I wrote longer (straight-line) programs, I found that the instructions generated by the compiler continued to look great—just how I’d have written it by hand. psl couldn’t handle general control flow but things were quickly getting interesting.

Enter volta

The shading language idea faded as the idea of writing a general-purpose

SPMD language targeting CPU SIMD instructions started to grab me: maybe

I could take a whack at that problem, since the people we were talking to

on the Intel compiler team certainly weren’t going to. When they weren’t

telling us graphics troublemakers “we already did it” (#pragma simd),

they would say “it won’t work” or “it’s impossible”, logical

inconsistencies between those positions apparently not a worry.

They were the compiler experts, so at that point I thought it entirely possible that I’d go down this road and find that they were right all along and that there was more to this than I understood. Again, I’d never actually written a compiler before. That outcome would have been fine as well, something new learned about computing, and new respect for their position.

Going back to Hamming’s acorns, I’d never have decided to take on the “write a SPMD compiler for CPU SIMD” problem from the start, but now I’d found that I had hacked myself into place where it seemed conceivable. I had built up enough infrastructure that I could envision a long series of small steps that would get me somewhere interesting if they all worked out, and I had enough confidence that LLVM wouldn’t let me down to be willing to keep betting on it for the code generation part.

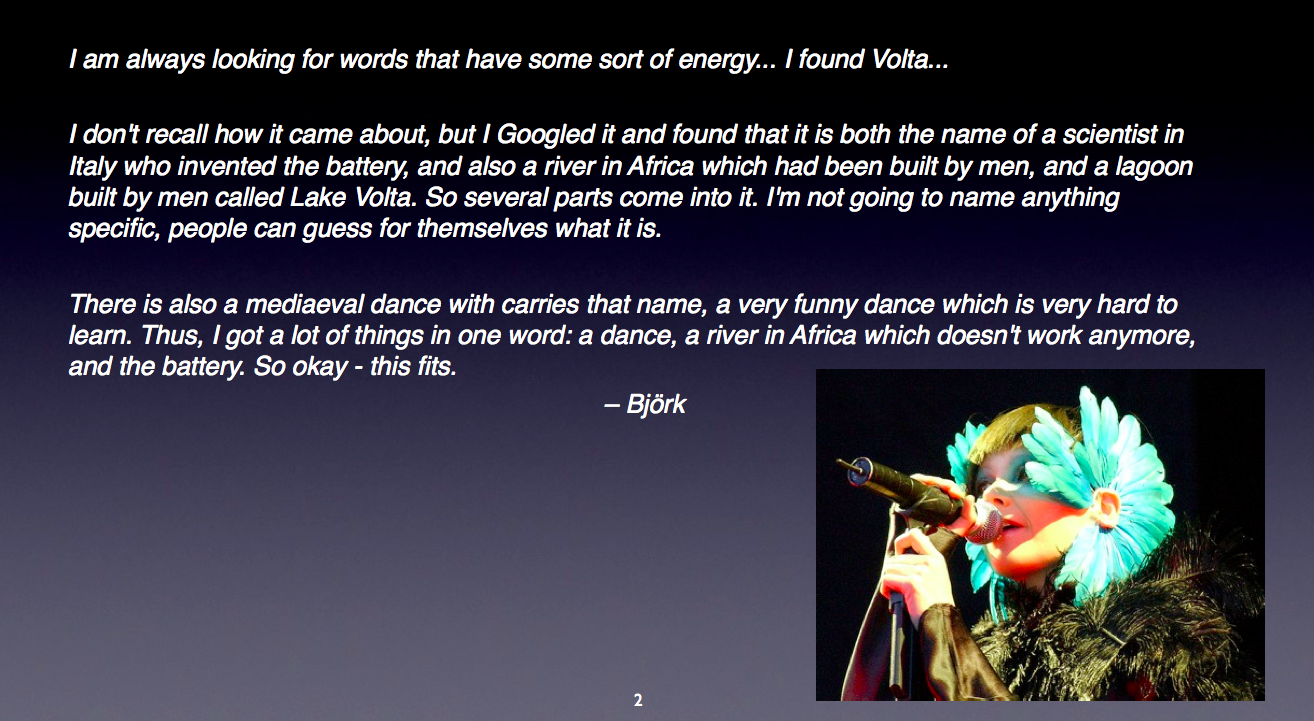

Once I had a more concrete goal, the most pressing issue was naturally to rename the thing; “psl” wouldn’t do any more. As one does, I turned to Björk for inspiration. Surely there was an album title or song name I could grab for this thing—a bit quirky, a little exotic, but suggestive of something really cool.

Passing up on Eat the Menu, I settled on “volta”.3 I liked the sense of electricity and energy, and, even better, I found an amazing quote from Björk explaining why she had chosen the name for the album. I’d start presentations at Intel about it with this slide:4

Ok, this fits. Sounds good for a compiler, too.

Next time, we’ll cover critical early managment support, and a little bit about the basic idea of SPMD on SIMD. Then, another exciting exciting interaction with the Intel compiler team when I shared early results!

notes

-

As it turns out, this is where things are for me in my current forays into machine learning for rendering. I’m just learning how to use TensorFlow well and trying to reimplement a few papers that other people have written about denoising. Sometimes I feel like I instead ought to be presenting a grand vision of ML for rendering, full of detailed plans and deep insights. Fortunately, Google has been quite supportive of the approach I’ve taken, which I trust will work out well in the end, even though I don’t feel particularly visibly productive at the moment. ↩

-

Apologies to Tomas, Jacob, Robert, Jon, and Petrik if that recollection is wrong and I’ve misrepresented their feelings about the Swedish national delicacy. ↩

-

Fun fact: in 2012, after hearing me mention ispc’s original name, Dave Luebke casually asked me where that name had come from. At the time, I wondered if “volta” might be a code name for a future NVIDIA GPU. (They’d already launched Fermi and Tesla, so it wasn’t unimaginable that they’d choose Volta since there was kind of a common thread of scientists who’d worked on electricity and power there.) Indeed, in 2013 Volta was announced on their roadmap. It shipped in late 2017. ↩

-

Another fun fact: as of my departure (2012), slide decks were still called “foils” at Intel, the name they’d had since the days back when presentations given using overhead projectors. I imagine this nomenclature is still in use.

(CC BY-SA 3.0, mailer_diablo) ↩